“I knew what it was like to want a book and to buy it, but I had forgotten what it felt like to amble among the library shelves, finding the book I was looking for but also seeing who its neighbors were, noticing their peculiar concordance, and following an idea as it was handed off from one book to the next, like a game of telephone. […] On a library bookshelf, thought progresses in a way that is logical but also dumbfounding, mysterious, irresistible.”

Susan Orlean, The Library Book (Atlantic, 2019)

When librarians enthuse about classification systems to those uninitiated in the profession, there is not a small chance they will be met with words to the effect of “who cares?” Yet, as American journalist Susan Orlean reminisces, a reader with classmark in hand scanning library shelves for the matching letters and numbers from the catalogue they recently jotted down (or more likely today, screenshotted) will often happily encounter related neighbouring books they might have never heard of and did not know they wanted. This possibility for serendipitous discovery comes from a process of classification: defining a book’s subject and representing it with a brief, alphanumeric code. The outcome: a singular, linear sequence guiding readers through the universe of knowledge. Our recent survey of Queens’ students found that around a quarter of undergraduates browse library shelves to find books to read for their studies, and so, consciously or otherwise, interact with classification systems.

However, the systems used to classify libraries are often slow to change, with their terminology and hierarchies betraying the prejudices and biases of their conception’s sociohistorical context. Eurocentricity and imperialism permeate the classification in the War Memorial Library, and vestigial racism lingers on in certain places. As part of our efforts towards decolonisation, we have taken some steps to rectify this, but there is still much more to do. This blog post discusses some of the issues we have spotted, some changes we have made, and some problems still to tackle.

Bliss

Queens’ War Memorial Library is classified using the Bliss Bibliographic Classification, named for the devisor of the 1940 first edition, Henry Evelyn Bliss, though much was changed in the currently used 1977 second edition[1]. Queens’ is one of 5 Cambridge college libraries using Bliss, and fewer than 20 libraries use the system at all. Like the Dewey Decimal System, Bliss aims to be a universal classification, capable (at least in theory) of finding a place for any book on any subject. Unlike Dewey’s rigid structure, Bliss provides more flexibility to the classifier, allowing alternative locations to suit the library. Classmarks beginning with the letter Y, for example, denote books on the language and literature of the preferred language of the library (English in our case), with other languages appearing in W and X; in the politics section, RS is for the politics of the home country of the library, whereas RT is for the politics of foreign countries. This means that the UK and the English language are given special status in our classification, giving rise to the question: should a classification system aim for objectivity in its organisation of the entire world of knowledge? Or should it reflect the distribution of subjects in a particular collection? Arguably, the answer lies somewhere in the middle.

The Bliss system is still incomplete, leading Queens’ to create local modifications and patches to cover the gaps. While this estranges Queens’ from other Bliss libraries, it does give us even more freedom to reconstruct the system. Furthermore, even when the original Bliss structure remains intact, it is always in a librarian’s power to change the classification labels and descriptors we use on signs in the library and on our website.

Race

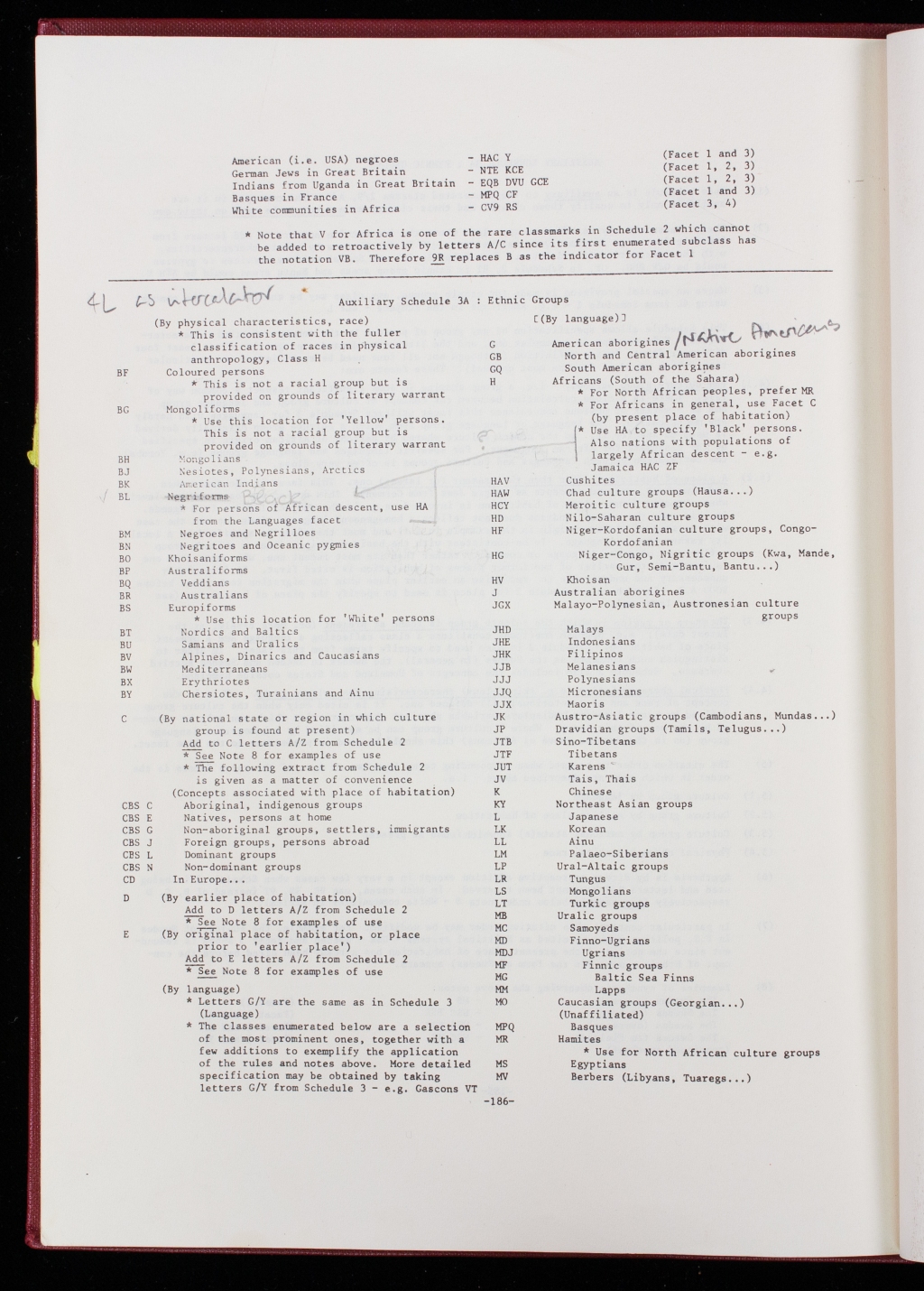

The introductory volume to Bliss contains several auxiliary schedules. These are general classifications of topics—such as geographic areas, chronological periods, forms and genres of printed works—that facet the main subject classes and cannot be used in isolation. One such auxiliary schedule is for ethnicity, which even classifies people into racial groups.

While definitions of racism may differ, all arguably include the assumption that groups of human beings can be categorised into ‘races’ which share common inherited attributes. Bliss’ racial categories may appear more befitting to the 1870s rather than 1970s, yet the library has continued to use these in its classification. Back to black : retelling black radicalism for the 21st century / Kehinde Andrews, for example, has the classmark RDR BL which is the notation for Politics—Collectivities in politics—Ethnic & racial groups—Negriforms (a now obsolete and unscientific anthropological term[2]). While the language is unacceptable, it is often necessary to acknowledge racial groupings: we need to reckon with the social reality that racism exists and accurately describe the subject of works on racial politics and the Black experience. However, it is imperative that we change classification underpinned by deeply outdated theories. One possible solution is to use the ethnolinguistic and geographical categories rather than racial ones, and so the above book could be classified as RDR H, substituting sub-Saharan Africa for Negriforms. Obviously there are flaws and complexities in this proposal, and ideally we would have guidance from students and the fellowship.

History

Our history section is the most Eurocentric. We have a subsection for European history (LZ), divided into expected historical periods: Medieval, Renaissance, Reformation, Industrial Revolution, and so on. Our world history subsection (LMZ) does not have its own subdivisions; it states instead: ‘build from LZ Europe’, i.e. use European historical periods for the whole world. Does this not contradict the very concept of the field of world history when the classifier sees the world from the point of view of only one of its continents?

Further to this, Queens’ faced the same problem as Jesus’ Quincentenary Library[3]: often histories of former European colonies were classified under the coloniser, rather than the national history of the colonised. The question at hand was: should books about French West Africa, for example, go under MBZ (History—France—Empire) or OZ (History—Africa)? Our decision was that if a book was mainly about the French colonisers it stays under France, but if it was mainly about the colonised people it would be moved to African history.

Regarding the library’s signage in the history section, it may not have escaped the attention of Irish students at the college that Irish history appeared under the section heading N: British History, similarly to the case at Pembroke College Library[4]. Furthermore, this only included books about England in the pre-18th-century classes, with pre-union Scottish and Welsh history pushed to the end of the section with English local history. This structure implies that the United Kingdom is a successor state to the Kingdom of England only. While we have not changed the structure, we have updated the signage to N-NW: British & English History and NX-NZ: Welsh, Scottish, & Irish History to temporarily provide clarity. One might say that treating Ireland as an equivalent to Wales and Scotland in the classification hierarchy implies the country is still within the union, and that Ireland could find a better home in the M section for histories of European nations. This could be a future reclassification project if it is decided that the history of Ireland can reasonably be separated from Great Britain.

Languages

One of the first targets for reclassification was the languages and literature sections. Signs in the library divided foreign languages into western and oriental categories. Not only is this orientalist and pseudo-linguistic, it can be confusing to a reader. Are Hungarian and Finnish, members of the Uralic language family spoken in Europe, western? What about Farsi and Hindi, related to the majority of European languages – are they oriental? And where could one find indigenous American languages, which come from as far west as one can be in the world? We updated these categories to Indo-European and Non-Indo-European. While some concern was raised that this might be less clear to the library user, we decided it would not serve to patronise students by assuming a lack of knowledge. One could argue that librarians’ noble quest for accessibility and ease of understanding risks oversimplification.

Furthermore, non-European literature was classified with less granularity, not ordered into chronological periods and not separated into separate language sections. With the advice of the Queens’ AMES director of studies, Farsi and Arabic literature has now been periodised, with subsections based on periods in the literary histories of those languages. Latin-American Spanish and non-European Portuguese literature were also treated with less care than Iberian literature, with Brazilian Portuguese works sort of lumped together with those from Hispanic America. We have now structured this by language, then by country, then by period, like is done with European literature.

This lack of specificity also applies to literature in English from outside England. Updates have been made to Welsh, Scottish, and Irish literature in three ways: firstly, our signage clearly distinguishes this section as Welsh/Scottish/Irish literature in English or Scots, to acknowledge that this is only part of the multilinguistic literature from the Celtic nations; secondly, it has also been periodised; thirdly, we moved books that were predominantly about literature in Celtic languages to the relevant section in X, as there were a couple of instances of confusion between Scots and Scots Gaelic. Still to change is the treatment of African literature in English, which is found in a “postcolonial” literature section.

There remain, however, limits in our ability to effectively classify some foreign-language material. While the Queens’ library team collectively has at least some knowledge of Ukrainian, Polish, Latin, French, Spanish, German, Dutch, and Flemish[5], it remains an inevitability that classifying books in non-Roman and non-Cyrillic scripts especially will be less specific and occasionally inaccurate.

Politics

Given that the current edition of Bliss began publication in the 70s, the classification of sovereign states still incudes the Soviet Union, with Ukraine as a subordinate constituent part. To reflect the modern reality that Ukraine is an independent country, books about Russia or Ukraine in the politics section, previously under the classmark RTN, have been split into separate classes: RTN A for Russian politics, RTN H for Ukrainian.

An article on the problems with the classification system in the War Memorial Library could continue indefinitely. It could touch on how paedophilia appears next to bisexuality in the K: Society section, or how books by or about women are often distinguished as such (e.g. Philosophers—Women) while books by or about men are treated as the standard (just Philosophers). Although some issues have been identified here, not all have been dealt with yet. Once a new structure has been devised, the process of reclassifying, relabelling, and recataloguing the books is a time-consuming affair, though one which I hope to have justified is worth the effort.

If you agree that this system does not reflect the inclusive academic community Queens’ aspires to be, the librarians welcome any input college members have on this.

By Harry Bartholomew, Reader Services Librarian

[1] ‘Bliss Classification Association : BC2 : History & Description’ <http://www.blissclassification.org.uk/bchist.shtml> [accessed 26 April 2023].

[2] S.O.Y. Keita and others, ‘Conceptualizing Human Variation’, Nature Genetics, 36.11 (2004), S17–20 (p. S19) <https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1455>.

[3] Rhona Watson and Alex Perkins, ‘Decolonisation Project in the Quincentenary Library, Jesus College, Cambridge’, Decolonising through Critical Librarianship, 2021 <https://decolonisingthroughcriticallibrarianship.wordpress.com/2021/12/01/decolonization-project-in-the-quincentenary-library-jesus-college-cambridge> [accessed 26 April 2023].

[4] Genny Grim, ‘Pembroke College Library History Collection’, Decolonising through Critical Librarianship, 2021 <https://decolonisingthroughcriticallibrarianship.wordpress.com/2021/05/24/pembroke-college-library-history-collection> [accessed 26 April 2023].

[5] These languages are ordered as they would appear on our shelves.

Leave a comment