By Harry Bartholomew, Reader Services Librarian

Doughnut-economist, Kate Raworth, famously shows in her delicious model the sustainable zone in which the global economy meets humanity’s needs without exceeding the finite planetary ceiling.[1] Applying this template to Queens’ library collections, the sweet spot for book provision surpasses the threshold of our users’ information requirements while contained within the physical limits of our shelves. In a small and cosy library like ours, the dough is miserly thin with a overly large hole: the absolute minimum number of books needed for a comprehensive modern academic library collection is stiflingly close to our shelving capacity. This leaves us in a claustrophobically tight spot: new acquisitions often must be shoehorned into the sparse gaps on the shelves, and mustering enough space for the steady inflow of fresh material can make daily shelving an onerous slog. Left too long, and our students will find themselves wading through densely packed, outdated, degraded books in their search for quality information sources. A project for sustainable storage to avoid critical overspill began last summer, as librarians worked to relocate a significant portion of the collection to closed-access stores; at the same time, we took the first steps on an even longer journey to better prepare our collection for a linked-data future.

Queens’ War Memorial Library has over 36,000 books on the open shelves, primarily serving around 1,100 students representing the full spectrum of disciplines and levels of study offered at the University. While the recent ubiquity of electronic books has given us a little more flexibility in our collection development—it being no longer necessary to buy a hefty tome of essays of which one has been suggested as pre-lecture reading for a course with only 10 students across the university—students still expect to find a broad range of high-quality information in physical form on the open shelves. In addition to the facilitation of serendipitous discovery through browsing (discussed in our blog post on classification[2]), a college library’s carefully curated physical book collection impedes the atomisation of the student body—ever more a risk with increasingly online higher education—through the provision of a collective, shared, in-person learning experience. It also mitigates academic siloing due to its multi- and inter-disciplinary scope, a valuable benefit of the collegiate system. First-rate academic collections require active development; we cannot just stop when the shelves fill up.

This then brings us to weeding: the selection of materials for disposal or storage and arguably the most notorious source of library-related controversy in public discourse. Rarely a lunar cycle passes without online pitchfork-wielders decrying public library withdrawals as akin to the burning of the library of Alexandria.[3] The question of how to fit everything in the stacks is left rhetorical. Cambridge libraries have been targets of freedom of information requests prying into whether we have taken down items from public view due to pressure from a “woke agenda”. Nevertheless, librarians must prune our stock. Weeding guides for librarians tend to focus on three broad criteria: information obsolescence, degraded material condition, and poor circulation,[4] and broadly, these have been applied to our project. We should clarify here that we have not just written basic criteria and clicked “run” on a report to generate a list of weeds, but rather use them as guidelines when considering the merits of each item individually. Many books that have not been issued by students in recent years may still be of value for quick reference within the library.

However, a starting point was needed: a thoughtful weeding project carefully considering the merits of each of the 36,000 items on the shelves would be impossible to do at a rate matching the inflow of new material. A filtered shortlist was produced, featuring only items that have not been bought or borrowed in the last 10 years and were published before the 21st century. These were then sorted into decade of publication from earliest to more recent, and within decades in classification order for easier navigation around the library. The oldest books on the WML’s open shelves are from the 1830s, and many mid-19th-century books are still in decent condition and circulating well. Approximately one third of items we have considered against our criteria have been selected for relegation to closed access, the majority judged to be of continuing value to the openly browsable collection. These judgments were not made by librarians alone: Queens’ academic staff have played an active role in curating the sections in their subject area.

It would be easy, once a book has been selected for storage, to amend its location information and store it away, possibly never to be read again. However, it ought to be stressed here that items selected for storage are not all deemed unimportant, many are books of such importance that the risk of deterioration as openly borrowable items had to be mitigated. Therefore, the second phase of the project, recataloguing the items, is crucial to ensure their continued discovery and use. Many older items in the collection, published before the digital age, have truncated and incomplete metadata: many lack authorised name and subject entries, have inadequate publication information, and ignore the copy-specific provenance traces left by donors and former owners. During the transition to a unified library catalogue across the collegiate university, such poor records for Queens’ books could not be merged into those from other libraries, leaving many of our books shamefully hidden in plain sight with users unable to see Queens’ holdings on some catalogue records for books we had in the library.

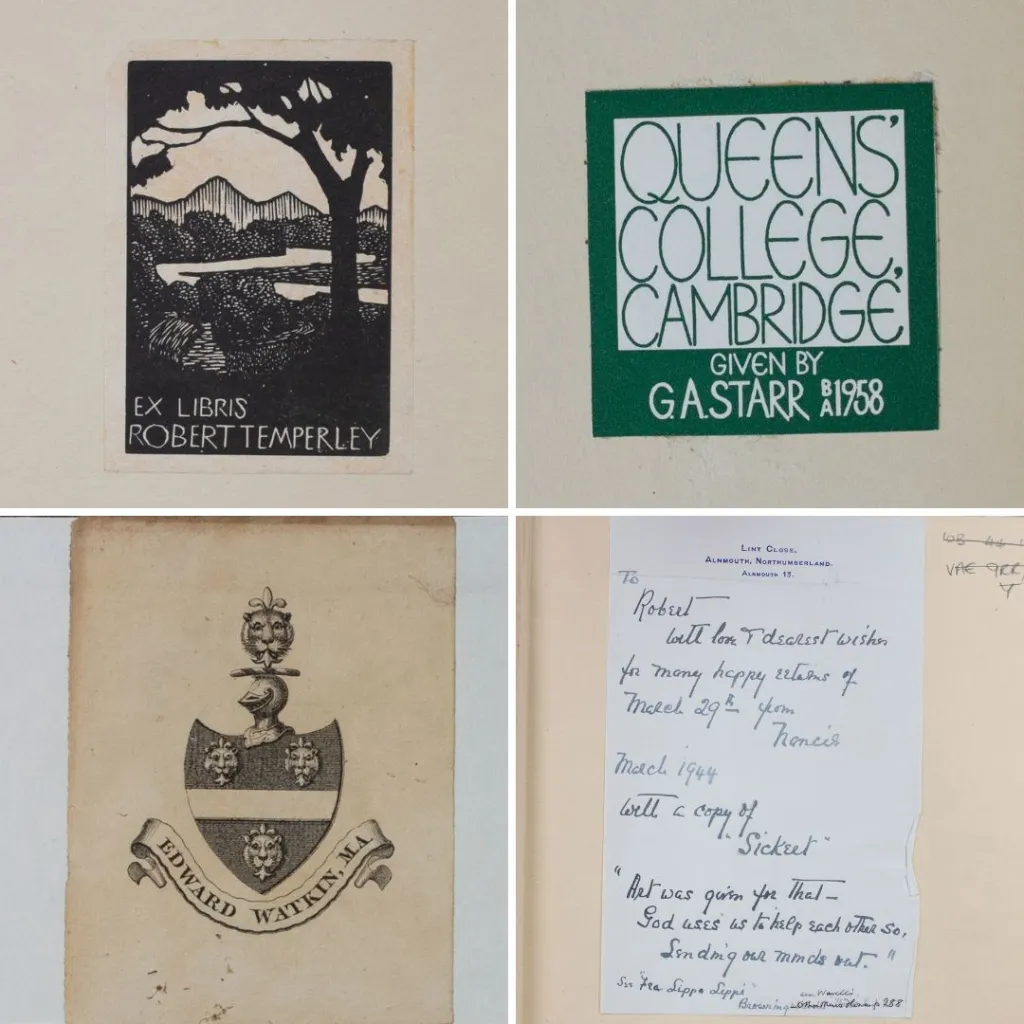

Our detail-rich recataloguing firstly merges our records with those for the same book in libraries across Cambridge, piecing together fragments of metadata from the pre-ISBN era. We then update them according to the modern RDA cataloguing standard, adding in any missing or incomplete bibliographic data. Our hope is to better prepare our metadata for the future transition to a multi-level linked-data model, such as BIBFRAME.[5] Lastly, we make note of our books’ provenance, bringing into view a fuller picture of the interaction of student societies, academic staff and alumni with the college library. One fascinating rediscovery is the 1950 bequest of Robert Temperley O.B.E., who matriculated at Queens’ in 1876. Alongside a gift of sculptures, paintings, and drawings, Temperley’s donation of 1,000 books similarly comprises mostly beautifully illustrated volumes on the visual arts.[6] As of April 2024, only 72 Queens’ books have been identified as part of the Temperley donation, browsable on the catalogue,[7] but our recataloguing project hopes to track down the rest.

Now more likely to appear in catalogue search results, our records for closed-access books also now link to a request form. The project has already yielded fruit, as we begin to receive retrieval requests for once stagnant items now rehomed in closed-access areas.

Familiar to librarians the world over, Ranganathan’s 5th law of library science states that the library is a growing organism.[8] Much like living cells, library books slowly replenish over time. Our annual book turnover rate is similar to that of neurons in the human hippocampus: around 1.75%.[9] We would say that a library’s comparison to a neural network is fitting.

[1] Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think like a 21st-Century Economist (London: Random House Business Books, 2017).

[2] Harry Bartholomew, ‘Obsolete Orders: The Need to Reclassify Queens’ War Memorial Library’, Queens’ College Old Library Blog, 2023 <https://queenslib.wordpress.com/2023/05/15/obsolete-orders-the-need-to-reclassify-queens-war-memorial-library>.

[3] This is hyperbolic, but the following sources should provide a flavour of the weeding discussion: John N. Berry, ‘The Weeding War’, Library Journal, 2013 <https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/the-weeding-war-blatant-berry> [accessed 18 April 2024]; Tracey Taylor, ‘Berkeley Library Chief Quits Amid Furor Over Book “Weeding”’, KQED, 2015 <https://www.kqed.org/news/10665724/berkeley-library-chief-quits-amid-furor-over-book-weeding> [accessed 18 April 2024]; Rebecca Vnuk, ‘Weeding without Worry’, American Libraries Magazine, 2016 <https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2016/05/02/library-weeding-without-worry/> [accessed 18 April 2024].

[4] ‘Collection Maintenance and Weeding’, American Library Association, 2017 <https://www.ala.org/tools/challengesupport/selectionpolicytoolkit/weeding> [accessed 18 April 2024]; Peggy Johnson, Fundamentals of Collection Development and Management, 4th edn (London: Facet Publishing, 2018), p. 197.

[5] ‘BIBFRAME – Bibliographic Framework Initiative’, Library of Congress <https://www.loc.gov/bibframe/> [accessed 18 April 2024].

[6] Queens’ College Record, 1951, p. 18 <https://idiscover.lib.cam.ac.uk/permalink/f/t9gok8/44CAM_ALMA51737126400003606> [accessed 18 April 2024].

[7] ‘Temperley Bequest (iDiscover Collection)’ <https://idiscover.lib.cam.ac.uk/primo-explore/collectionDiscovery?vid=44CAM_PROD&inst=44CAM&collectionId=81764878950003606>

[8] S.R. Ranganathan, The Five Laws Of Library Science (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1931), p. 326.

[9] K.L. Spalding and others, ‘XDynamics of Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Adult Humans’, Cell, 153.6 (2013), 1219 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.002>.

Leave a comment